DIAGNOSIS

Finding the answer: diagnostics communication and barriers.

Our community reports that interactions with health professionals can be frustrating. Here we outline the recommended methods for confirming whether someone has FSHD and provide some guidance on the steps to getting to a diagnosis. We also explore some of the common misconceptions that people with FSHD experience.

Health professionals, particularly in primary care, are dealing with high patient loads with very little time to devote to learning about conditions that are rare. Many would have had very little teaching of neuromuscular conditions in medical school and since leaving there would be little incentive to upskill unless they had a particular interest in this disease area. The symptoms associated with FSHD are relatively non-specific, this combined with the fact that FSHD is rare and the diagnostic methods not typical means many people who have FSHD can face years before they receive a definitive diagnosis.

Diagnosing FSHD: what are the steps?

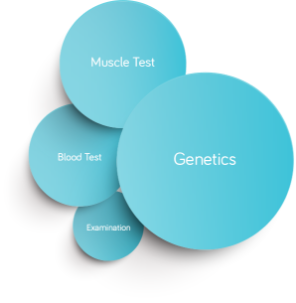

The diagnosis of FSHD is more than just getting a simple blood test. There are a number of steps that you will need to take to get to the answers you want. Your doctor will be able to help you through all of this. There are also a number of groups around Australia who can give you help and support.

HUNTING FOR A DIAGNOSIS

‘You can’t have FSHD, only males get FSHD’

The muscular dystrophies are a diverse group of diseases that cause muscle wasting. Each is a unique disease with a unique disease mechanism. Unfortunately there is a propensity to group them together and assume they are all similar.

People often assume that muscular dystrophy is something that only affects boys because of Duchenne’s Muscular Dystrophy (DMD). The reason DMD affects mainly boys is that the gene involved (dystrophin) sits on the X chromosome, or the female sex chromosome. Female children have two copies of dystrophin, to develop DMD you need two mutated copies. Having two mutated copies is rare and therefore DMD is very rare in females. For boys, who only have one X chromosome, if that copy of dystrophin is mutated they do not have a back-up copy to prevent the development of disease.

Most health professionals would have studied DMD during their training because it has several features that make it an excellent teaching tool for students to understand genetic basis of disease. Because of this they may think that DMD is the most common form of muscular dystrophy, or even assume that the features of DMD are shared by all other dystrophies. Some people may also be unaware that there are actually other muscular dystrophies.

Of course, FSHD as well as other dystrophies are equally likely to affect males and females because the genetic defects do not sit on the X-chromosome.

‘You can’t have FSHD because you don’t have *common symptom*’

The term facioscapulohumeral dystrophy was introduced in a 1950s scientific paper where researchers had studied the typical pattern of inheritance and symptoms of this dystrophy in a large family.

This pattern of symptoms being facial, shoulder and upper limb weakness. However, even in this publication the highly variable way FSHD manifests was observed.

The symptoms used to clinically identify FSHD may be what is usually seen, however, they should not be used to rule people out of a diagnosis of FSHD.

‘You can’t have FSHD, you don’t have any family history’

FSHD is a genetic condition that is passed from parent to child. However, a significant minority of FSHD cases are what is known as ‘sporadic’. That is, a mutation that happens spontaneously and is not inherited from your parents.

Family history may help identify conditions that should be investigated when someone presents with progressive muscle weakness, but lack of family history should not be used to rule people out of a diagnosis of FSHD.

‘There are no treatments for FSHD, so why do you want a diagnosis’

Access to treatment is only one reason to have a diagnosis. There are many reasons why getting a confirmed diagnosis is important to people.

- Giving your condition a name is powerful – it means you have an explanation of the symptoms you are experiencing. It can mean being able to tell your workplace exactly what is wrong, empowering you to ask for assistance.

- Having a diagnosis means that you have a clearer idea about what your future may look like, and the opportunity to plan for that future. For example, does your home have stairs or poor access points, is your workplace accessible, are you planning on starting a family? There may not be any treatments available at the moment, but that doesn’t mean that there aren’t things that can be done right now to improve your quality of life and prevent deconditioning and deterioration. <link to ‘Managing FSHD’>

- Many assistance measures that are available for people with a disability are only open to those with a confirmed diagnosis. Things like access to personal care assistance, employment assistance and other medical benefits may only be available if you can present evidence from your doctor confirming you have FSHD.

- Access to clinical trials. Many trials require genetic confirmation of FSHD before they will consider you for clinical trials. If you would like to be involved in trials it may be a good idea to get a confirmed diagnosis. Clinical trials give you access to new treatments being developed for FSHD very early in the development process.

“Getting a diagnosis of FSHD will affect my health insurance”

The laws governing health insurance are clear. Insurers must continue to provide cover for people who have pre-existing medical conditions. Premiums for private health insurance will not be affected by a genetic diagnosis.

What will be affected are policies like life insurance. The Centre for Genetics Education has a fact sheet detailing the effects of a genetic diagnosis on insurance.

http://www.genetics.edu.au/Publications-and-Resources/Genetics-Fact-Sheets/FactSheetInsurance